How a few powerful hands control our economy

The (In)visible Hands

“The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.” — John Maynard Keynes

Beyond Supply and Demand

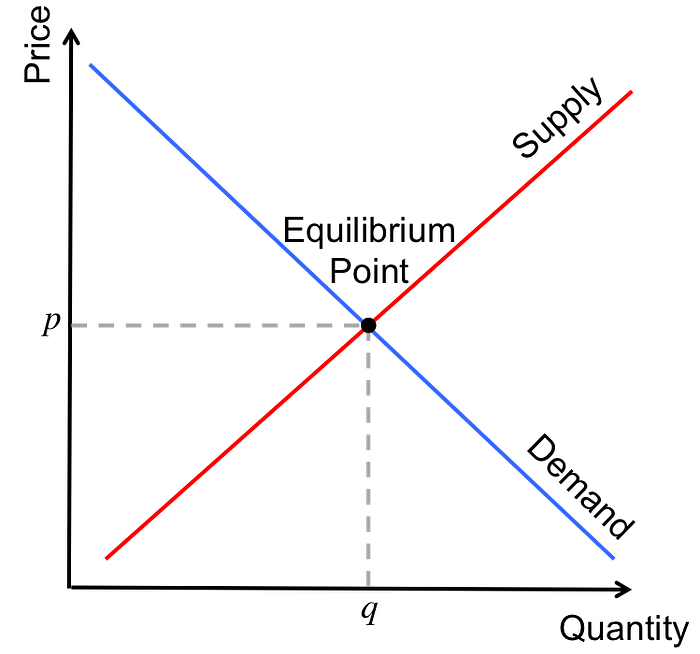

On the first day of Econ 101, I remember my professor drawing a simple graph that resembled an ‘X’ on the chalkboard. He explained, ‘As demand goes up, prices go up.’ It wasn’t long before I realized the entire foundation of economics relied on this concept of supply and demand.

But how well does it actually describe the modern economy?

Even when demand is stable, prices still rise. Eggs, beef, electricity, insurance, and streaming services have all reached unprecedented levels.

Of course, some of that is due to supply shifts: the bird flu, feed costs, inflation, and tariffs.

But almost everyone agrees that prices today feel excessive.

If the supply and demand model worked as intended, competition would drive prices down. Instead, most industries are thriving on higher prices, higher profits, and fewer players.

The truth is, supply and demand no longer describe the economy we live in.

Maybe it represented something long ago. But today, technology and consolidation have rewritten the rules. Competition is choked off, and whatever control consumers once had has disappeared.

Markets now behave as firms want them to, and consumers have to adapt.

If there’s a company policy you don’t like, if they’re implementing AI against your wishes, if the CEO is making an unheard-of-salary, what can we really do?

The Invisible Hand Illusion

Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand metaphor describes the idea that self-interest, guided by competition, benefits society as a whole. In theory, producers must offer better products at lower prices to attract customers, creating efficiency through the pursuit of profit.

It’s an idealistic world that’s simple, fair, and full of choices. But to me, the economy feels a little more one-sided.

When the supply and demand model was popularized in the 1890s, most markets were based on common goods like wheat, coal, and cloth. There were plenty of sellers, little advertising, and no brand loyalty. Maybe then, you could see how prices reflected supply and demand.

But now, it’s more and more often that only one or two companies provide certain goods and services.

Technology shows this best. Once a company gains an online presence, it’s hard for anyone else to compete. There aren’t many alternatives to software like Adobe, search engines like Google, or online marketplaces like Amazon.

And social media giants like Facebook benefit from the network effect. The more users that are on the platform, the more others are pressured to join.

When only a few firms control a market, price is not a signal of competition. It’s business strategy and coordination.

Every megacorporation today doesn’t need to participate in the market- they create it. They set the expectations, manipulate perception, and manage your willingness to pay.

The supply and demand model still dominates economic thinking because it’s tidy. It’s how we justify capitalism as self-regulating and where markets follow a natural law guided by an Invisible Hand.

But that’s not the world we live in. The textbook “exceptions” have become the norm. Maybe it’s time our economic models caught up with reality.

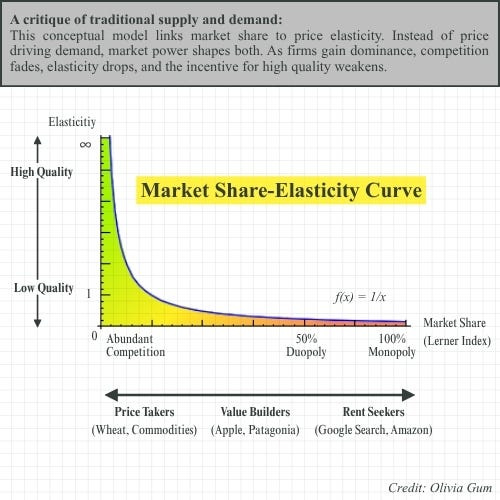

Introducing the Market Share-Elasticity Curve

Let’s forget about equilibrium and efficiency. Let’s think about power.

Every major company, from Google to Walmart to Pfizer, measures its success not by how much it produces, but by how much of the total market it controls.

Once they control enough, they decide what the “right price” is.

This is where market share elasticity comes in.

Traditional elasticity measures how sensitive consumers are to price changes. If the price rises, demand falls by a certain %.

But in concentrated markets, price sensitivity is determined by how much choice you have.

When dozens of competitors exist, prices are elastic. Customers can switch if they’re unhappy. But when one or two firms dominate, demand becomes inelastic no matter the price. You stay because you don’t have a choice.

And here’s the kicker: As companies gain market share, their own behavior becomes inelastic, too.

When Netflix recently implemented simultaneous price hikes and a crackdown on password sharing, many expected a significant customer drop-off. Instead, these changes were absorbed by the market with minimal resistance, highlighting the power gained from market domination.

Once they dominate, companies no longer feel the need to innovate or compete on quality because demand is already secured. Even if it’s not intentional, growth brings complacency as oversight of maintaining the product or service’s original quality declines.

In other words, market share is often prioritized above profit.

The Illusion of Choice

I get so frustrated when economists still talk about supply and demand as if we’re all standing in one big farmer’s market, walking from booth to booth choosing who deserves our dollar.

That’s not how modern capitalism works. You can’t really switch search engines, or health insurers, or app stores. The choice has already been made for you.

On the shelf, it may look like the world offers endless choices. But behind the screen, megacorporations have turned competition into choreography.

Prices rise together, quality declines together, and consumers keep dancing to the illusion of choice.

Companies know exactly how much friction you’ll tolerate before you give up. They know your switching costs (your data, your habits, your subscriptions) and they price you, not the product.

As Keynes said, “The difficulty lies not in developing new ideas, but in escaping from old ones.” And nowhere is that truer than in economics. We cling to a model so outdated it’s made us blind to the systems actually running our lives.

It’s time to stop pretending the Invisible Hand still guides us. The hands shaping our economy are visible, deliberate, and powerful. Until economics recognizes that, it can’t explain the world we actually live in.